Even though I live in the authentic Wild West, just 45 minutes down the interstate from Tombstone, I have never been a huge fan of Westerns. When I was a child in Maine, which is as far from the West as you can physically get, my father and grandfather used to watch them religiously on TV, especially Gunsmoke and Bonanza and Have Gun Will Travel. I grew up with the tropes and the visual and verbal vocabulary, but they didn’t capture my imagination the way science fiction and fantasy did.

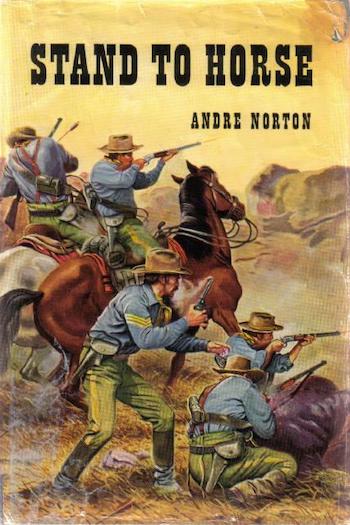

Stand to Horse was published in 1956, in the heyday of the TV Western. It reminds me of 1962’s Rebel Spurs, which is set in approximately the same part of the world, and in some ways it’s a prequel to the prequel, Ride Proud, Rebel! (1961). These two earlier novels are set in and after the Civil War. Stand to Horse takes place in 1859, with multiple references to the conflicts that will explode into full-on war by the spring of 1861.

The novel is one of Norton’s “do it once, then do it over again” plots, with a standard Norton orphan protagonist. Young Ritchie Peters has joined the U.S. Cavalry after his father dies and his wealthy family goes bankrupt. His mother and sisters have taken shelter with relatives. The only place for him to go is the military, and he’s been shipped to the far ends of the earth, to the dusty outpost of Santa Fe.

There he makes a friend or two, acquires an enemy or two, and is sent out on two disastrous scouting ventures, one in the winter right after his arrival, and one in the summer. Both result in casualties among men and horses, pitched battles against the Apache, and dire effects of weather, thirst, and starvation. It’s brutal country, with brutal inhabitants both Native and colonialist, and it does its best to kill our young protagonist.

This is a dark book in a grim though often starkly beautiful setting. Ritchie is there mostly just to survive, and he keeps being called on for desperate ventures in impossible conditions. Every time it seems as if things can’t get any worse, they do—and then they get even worse.

From the perspective of 2020, the classic Western has distinct problems. Colonialism itself is no longer accepted in the way that it was in 1968. Manifest Destiny, the White Man’s Burden, the imperative to conquer empty lands and civilize the savage inhabitants—these ideas have all been seriously rethought.

There are faint hints in the novel of a different way of thinking. Once or twice, Norton shows that she researched the culture of the Apache, and we get a glimpse of them as human beings. But for the most part they’re the dehumanized Enemy, vicious and savage (a word she uses more than once) and cruel, who do hideous things to white people. When the cavalry decides to attack an Apache stronghold, they note that the women and children will be left homeless and forced to starve, but they shrug it off. Tough for them, but that’s the way things are.

Ritchie manages to rescue a small ferocious boy, but he’s depicted as alien and essentially an animal. He’s tamed enough to get him back to white civilization, and then he’s handed over to a missionary to be indoctrinated in white culture and turned into an Army scout. In the same way, hunters might tame a wolf cub and teach him to turn against his own species.

In 1968, this rescue would read as an act of kindness. Ritchie saves a life, though it nearly kills him when the boy bites him and severely infects his hand: he gives the savage child the opportunity to become a civilized man. In 2020, this is an example of one of the worst crimes against Native people, ripping them from their families and destroying their culture.

This is not a comfortable book, and it’s not particularly pleasant to read. Mostly it’s about awful people undergoing awful things in a brutal and unforgiving landscape. I confess that if I hadn’t had to read it for this series, I would have stopped long before the end. But I did push through, and for most of the way, I tried to figure out what the point of it all was.

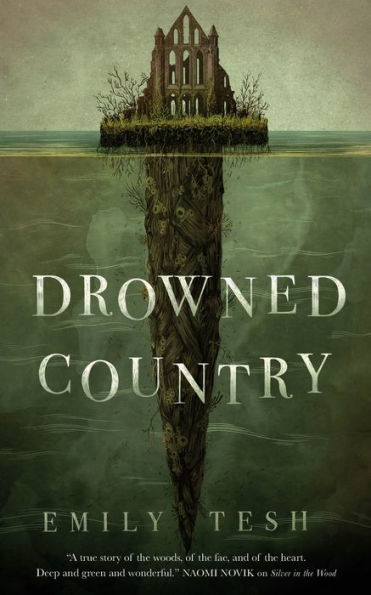

Buy the Book

Drowned Country

The end gets a bit triumphalist about a man falling in love with the land he lives in. That seems to be what Norton thought she was aiming at. Ritchie the New Englander learns to love this alien land, until he becomes a part of it.

I get that. I’m a New Englander, too, and I moved to the Southwest for my health, and learned to love this landscape that is so very different from the one I was born in. All the colors are different—the shades of green, the reds and browns, the stark blue of the sky. It’s hard country, full of things that will stab or poison or kill you. It’s stunning, and it gets into your blood, until you can’t really live anywhere else.

Those parts of the novel spoke to me strongly. The abandoned pueblos, the remnants of great cultures now long gone, the people clinging to outposts and hidden canyons, that’s still here, even with the overlay of white expansion. There’s the sense that I’m part of the long invasion, too, though I feel very much at home here. Which makes it complicated.

There’s a lot of pretty decent horse stuff, since Ritchie is in the cavalry. Horses have personalities, and humans care for and about them. And mules. Mules get their clear and present say. As do a handful of camels, which come as sort of a surprise, but they are historically accurate.

But still I wondered what it was all for. The love-of-land thing comes in late. And then I realized.

This is a romance. I don’t know if Norton was aware of what she was doing, if she took some wicked delight in doing it, or if it just sort of happened that way. When Ritchie first sees Sergeant Herndon, he sees him in terms that in another novel would point to love at first sight. The clean-cut, smooth-shaven face in a world of hairy men, the lithe body, the sense of being just a cut above everyone else though he is not and emphatically will not let himself be addressed as an officer. That’s the language of love.

And it continues. Herndon singles Ritchie out, takes him along on critical missions though he’s an utter greenhorn, and in the end, in their very restrained and highly constricted way, they do get it together. Lying in one another’s arms. Facing death as one.

There’s even a triangle of sorts. The dashing, dissolute Southern gentleman, Sturgis, can’t stand the Sergeant. He takes Ritchie under his wing, screws him over but then makes up for it, and ultimately dies a noble(ish) death. At which point he has, in his way, come to respect Herndon, and also in his way, he sets Ritchie free to seek his real true love.

The happy ending does happen after all, and it’s not really about Ritchie falling in love with the land. It’s about who lives there, and whom he chooses to share it with.

Next time I’ll shift genres to one I actually like better than Western, the Gothic, in The White Jade Fox.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Since then she’s written novels and shorter works of historical fiction and historical fantasy and epic fantasy and space opera and contemporary fantasy, many of which have been reborn as ebooks. She has even written a primer for writers: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.

Thanks for reading this, so I don’t have to, and for sharp analysis!

Sometimes old books can seem shockingly out of step. For example, H Beam Piper’s Fuzzy books were almost the first SF I read that took manmade environmental change seriously, and they stressed that “people” can include more than Homo sapiens. And then everybody smokes all the time (and are casually sure tobacco is harmless) and women quit their jobs when they marry, etc., etc.

useless to say, well, that’s how things were then, when today’s readers are reading them. Maybe it’s the Suck Fairy getting at them.

Good essay.

Just for the record those are sooo not 1850s U.S. cavalry on the cover; more like 1890s.

One writer of cavalry adventures who has worn well in my eyes is James Warner Bellah, probably because he did not romanticize what the settlers and soldiers were doing. His fiction is hard to find these days, but you can see echoes of it in the John Ford westerns based on Bellah’s work.

Science fiction and Westerns in media are the same dang thing. Space opera and horse opera. The same tropes and everything. Roddenberry sold original TREK to Hollywood as “WAGON TRAIN in space.” STAR WARS is a pile of Western tropes in a nice pulp movie bow. Do I even have to mention FIREFLY? The creative talent for both genres moved back and forth with ease. The Western novel follows most of these tropes, too.

As prissy as Norton is about m/f romance, I seriously doubt she wrote this as a m/m romance. So, that’s really reaching for what the novel is about. A bro-mance, maybe. Friendship and warrior-bonding were very much a thing in her writing, though.

I wish someone would have pointed me at these Norton Westerns when I was first finding her science fiction. Much as I was sure I was a science fiction fan only, over the years I’ve found that if I like an author in one genre, I will also like the author in another. It seems that it is the author’s voice that captures me, more so than just the setting or characters.

@2 Good point, the weapons are also anachronistic. The first lever action Winchesters didn’t appear until 1866.

@1

It’s never useless to place past works in the proper context, i.e. the past, and understand how cultures change over time. Otherwise history can’t be properly studied.

” It’s brutal country, with brutal inhabitants both Native and colonialist, “

Interesting to note that the Apache were also invading colonizers, as they settled in the Southwest sometime between AD 1200 and 1500.

Going by The Prince Commands Norton had a knack for writing m/m romance. Did she realize what she was doing? Interesting question.

@8 As far back as pre-history, one band/tribe was killing another band/tribe who had killed another band. Humans are brutal, greedy piles of poop, whatever the color of their skin. Romanticizing or demonizing any group is silly.